Ever wondered what the world looks like through the eyes of a cockatoo, a giraffe, or even a butterfly? A recent study published in Trends in Ecology & Evolution set out to answer this question. Lead author Eleanor Caves explains that humans possess higher visual acuity than most animals, meaning many species see the world with far less detail than we do.

Over recent decades, researchers have been gradually uncovering how animals perceive the clarity—or lack thereof—of their surroundings.

The study, led by Caves and her team, compiled existing data on the visual acuity of roughly 600 species, including mammals, birds, insects, fish, crustaceans, and more. This comprehensive collection represents the most extensive database on animal visual sharpness to date.

Visual acuity, measured in cycles per degree, quantifies how many black-and-white parallel lines an animal can distinguish within one degree of its visual field. For humans, this translates to roughly the size of a thumbnail held at arm’s length, where we can resolve 60 cycles per degree.

To determine visual acuity in animals, scientists analyze the density of photoreceptors—light-sensitive cells in the retina—or conduct behavioral studies to observe how well animals can discern black-and-white stripes in their environment.

As cycles per degree decrease, so does the sharpness of vision. Humans with less than 10 cycles per degree are considered legally blind, while most insects are fortunate to achieve even one cycle per degree.

Australia’s wedge-tailed eagle, one of the most visually acute species, can detect nearly 140 cycles per degree, enabling it to spot a rabbit from thousands of feet above. Cats, while falling below 10 cycles per degree, excel in nighttime vision due to their enhanced sensitivity to light and color differences.

Cleaner shrimp, on the other hand, see the world in an incredibly blurry 0.1 cycles per degree. In total, the study revealed a staggering 10,000-fold difference in acuity between the sharpest- and blurriest-sighted creatures.

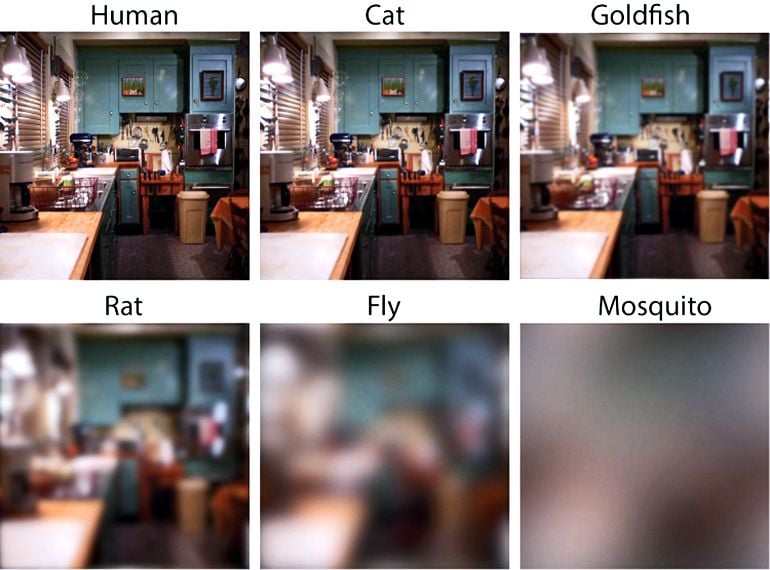

Using these measurements, researchers employed a software program called AcuityView to simulate how various animals perceive their environments. For example, the intricate patterns of a spider web may appear as a clear warning to birds while remaining virtually invisible to insect prey.

Though these simulations help humans understand animal vision, Caves emphasizes that they are not fully representative of what animals experience, as their brains process visual information differently from ours.

Rather than viewing the world as irredeemably blurry, animals with low acuity simply adapt to the information available to them. Caves notes that animals cannot process details they are unable to perceive in the first place, meaning their brains work with the visual cues that matter most to their survival.